Between 1954 and 1958 this would have been an easy piece to write. At the time, Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer had only his debut collection out,

17 dikter. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1954.

Had it been released in English it would, without a doubt, been titled 17 poems. 17 - and put here whatever your word for poems is - and it would have been the title also in your language. At that point a substack discussing his often dream evoking titles would have been a tiny paragraph, at most, but probably not even that. Today, however, with the works that followed, it is difficult.

Hemligheter på vägen.– Stockholm : Bonnier, 1958

Den halvfärdiga himlen. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1962

Klanger och spår. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1966

Mörkerseende. – Göteborg : Författarförlaget, 1970

Stigar. – Göteborg : Författarförlaget, 1973

Östersjöar. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1974

Sanningsbarriären. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1978

Det vilda torget. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1983

För levande och döda. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1989

Sorgegondolen. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 1996

Den stora gåtan. – Stockholm : Bonnier, 2004

Before I started to write, I thought I would present these titles and that would be the end of it. The Titles of Tranströmer. It would be the kind of post designed to be read from above, taking something solid, a firm grip on reality, like 17 poems, and then slowly dilute it. Allow more and more doubt, questions, and wonder to enter into the reader’s mind. Lost in a reality full of alternative motive and secret codes, you would feel like Tranströmer himself felt towards the end of, Porträtt med kommentar (Portrait with commentary, 1966), when he had managed to fix the idea of himself:

Men just som jag fick syn på JAG / But just as I saw ME

Försvann JAG och ett hål uppstod / ME disappeared and hole appeared

och genom det föll jag som Alice. / and through it I fell like Alice.

A friend describes that during the time of his mental illness the world filled up with signs and codes. Numbers, colors, messengers. It was as if it came a step closer, and revealed itself to him, chosen for whatever reason, in its full mysterious glory. During those times, normally a rather gregarious character, he would be humble and silent. He would pay attention to bums, postmen, and police; anyone marked with a way of moving, and certain glow in their eyes. He noticed upon how the birds would fly in certain directions. During these periods he would not go home, but sleep in parks in order to pay closer attention. There was a spiritual war going on that only he and a few select, high people, were aware of. Throughout everything was a message from God. The times he spent in the hospital was extra intense, everything there multiplied. He went through it with great dignity, reserve, and pride. A nod at someone was enough, or the way your toes were pointing. The hospital was like living inside the eye and from there any action could have disastrous effects. He was hovering beneath a wild storm.

Tranströmer, a physiatrist by profession, had the same ability to zoom in on mundane occurrences and make them mystical.

Jag öppnar den första dörren. / I open the first door.

Det är ett stort solbelyst rum. / It’s a large sunlit room.

En tung bil går förbi på gatan / A heavy car passes on the street

och får porslinet att darra. / and makes the porcelain quiver.

Jag öppnar dörr nummer två. / I open the door number two.

Vänner! Ni drack mörkret / Friends! You drank the darkness

och blev synliga. / and became visible.

Dörr nummer tre. Ett trångt hotellrum. /Door number three. A cramped hotel room.

Utsikt mot en bakgata. /View against a back alley.

En lykta som gnistrar på asfalten. /A lamp sparkles on the pavement.

Erfarenhetens vackra slagg. /The beautiful slag of experience.

(Elegi, Ur Stigar 1973)

Had I been strong like my friend I would present his titles and let them be. Each for himself! But, by reading them I find myself completely surrounded. It’s not an open field, it’s a deep forest. You will have to speak to get out of it.

The Trials of Translation.

For you who understood please turn to devour, while I will go on to dilute and destroy. Many accomplished poets have decapitated Tranströmer by bringing him into the English. But if what ought to be following a list of his titles is silence (and in this not even his own poetry did it justice), if after the titles there is no thing – ingenting – doesn't then also this have a tension to it? The silence we are in is a dense silence, which is almost the opposite of silence, since it is, much like my friend’s, a silence filled with words.

After 1970 most of his collections were brought into English, starting with Robert Bly’s take on Mörkerseende, Night Vision (1971). I like that more than the commonly available translation, Seeing in the Dark, by Patty Clane. The literary meaning is probably better in Clane’s take, since it is darkness, not night, and vision is seeing, and no other vision. But what Clane misses, and Bly gets, is that Tranströmers title is an ability, and not an act. It’s a gift. But, while Bly's Night Vision echos a kind of noir drama (Night Rider? City of Night?) Tranströmers mörker evokes darkness, somber shade, like, beautifully, in German, Dunkelheit. I guess more importantly when I read Mörkerseende I do not think of Night Vision, nor of Seeing in the Dark, but of whatever quality of the fly, or the bat, to see beyond what we are normally able to capture.

Östersjöar, that follows, was translated as Baltics by Samuel Charter in 1975, and then also by Robin Fulton in 1980. Baltics brings to mind “the Baltics”, the geographical name of the nations bordering The Baltic Sea. It is not the imaginary plural of that same sea that Tranströmer named his collection after. Like Mörkerseende, Östersjöar contain uncertain elements, the second even being a made-up word, probably never previously used, while Night Vision or Baltics have been washed in cultural and political use.

The following, Sanningsbarriären, was first wrongly translated as Truth Barriers in 1980 by Robert Bly, then correctly in 1984 by Robin Fulton as: The Truth Barrier. Det vilda torget, was brutally translated as The Wild Marketplace by John F Deane in 1985. While Tranströmer title, precisely meaning The Wild Square, speak nothing of commodity, Deane’s translation seems to be speaking of goods and trade, that get even more corrupted in an era when marketplace firstly brings to mind the trading sites of health insurance and labor. Yes, the marketplace is where we sell ourselves, while the square is that open spot in the middle of the city.

Then comes Tranströmer’s perhaps most beautiful title, Sorgegondolen, which gets translated as The Sorrow Gondola by Robin Fulton in 1997. (the title itself being a take on Litsz composition La Lugubre Gondola - the gloomy gondola). I take no issue with this translation; I only regret it being separated into three words. However, one can speculate on how it sounds for an English speaker, since for a swede the use of the gondola as an image is very rare. Apart from the mid-century restaurant in Stockholm, (KF's masterpiece that also needs a substack) Gondolen, I can't think of a single time I’ve come across it. And so, I can only hope that Sorgegondolen sails into all languages in the same manner, big and dark and over imposing, like a massive, opaque shadow, freezing all thought and conversation along the quay. Finally, there is the rather straightforward title and translation of Den stora gåtan as The great enigma by Robin Fulton in 2007.

At this part of the text, I feel downhearted. The simple list of titles and the feeling of reading them is not simple at all. A lot of work has gone into bringing them out, by people who holds this profession, and still, we are not nearly there. But, the attempt of poetry is just this: to speak the unspeakable. When we speak of poetry, we speak of a surface, meaning what reaches it, while the real movements, the real subject of the writing continues down below. The language is what comes to light. Transtömer himself describes this beautifully when he, in his acceptance speech for the Neustadt’s prize in 1990, said: (and I will translate here freely)

“Let me sketch two ways to look upon a poem. You may understand a poem as an exclusive expression for the life of language. The poem has organically grown out just that language in which it is written, in my case Swedish. In fact, it is a poem written by the Swedish language, through me. It is impossible to move into any other language.

Or a diametrically different way to see it: the poem as you see it is a manifestation of another, invisible poem. It’s a poem written behind the ordinary languages. And so, already the original version is a translation. To transfer it to English or Malayalam is then only a new attempt from the invisible poem to realize itself.”

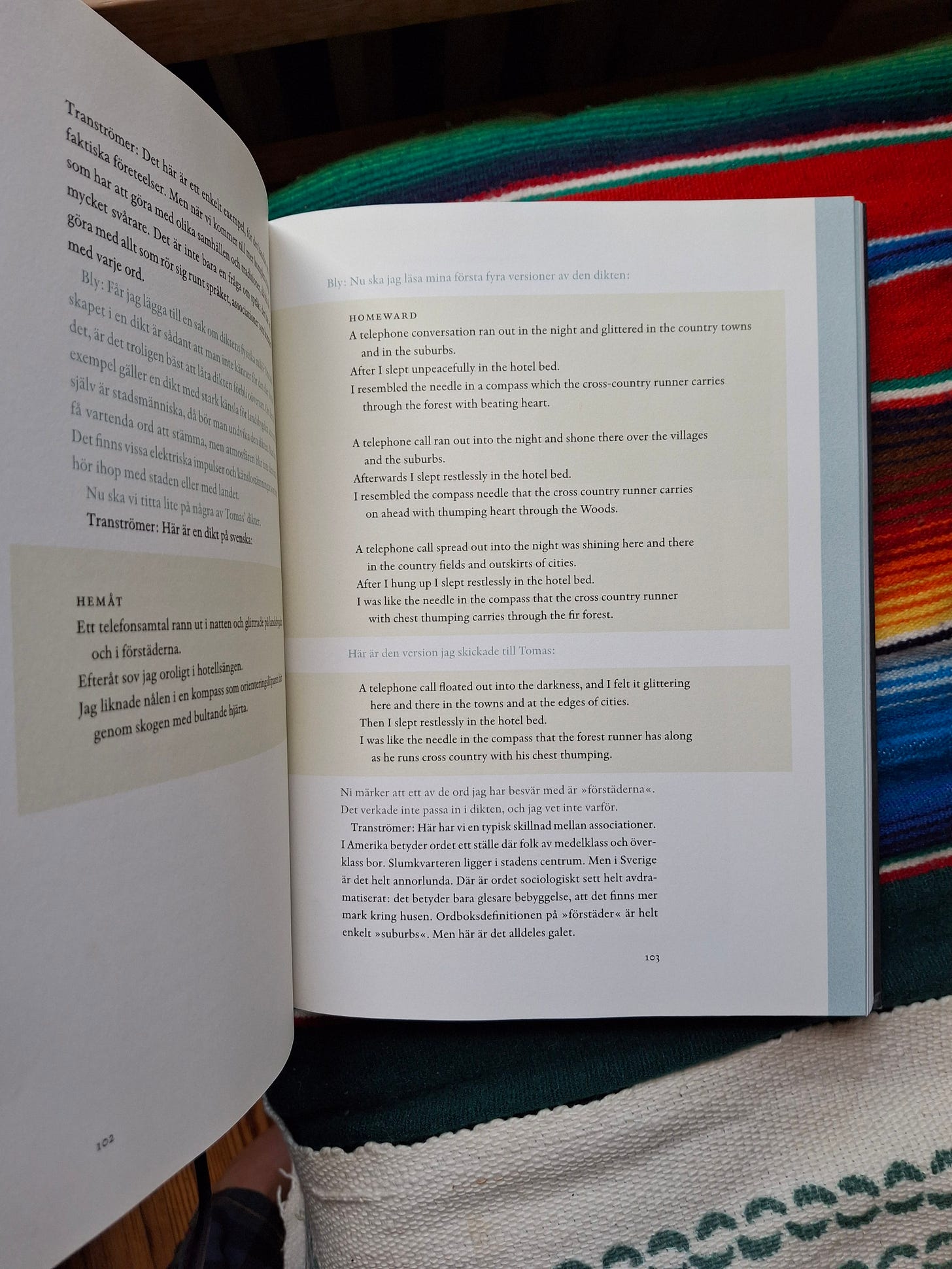

The most prominent translator of Tranströmer into English, Robert Bly, describes the process of translation as rather simple. The first part is to translate the words – which can be done with a dictionary – then make a rough draft. This can be flat and meaningless. If you don't feel anything for the poem, Bly says, leave it. Someone else with feelings for it can make the translation; if you feel nothing you cannot do it. (The other night I saw this done live by artificial intelligence, a cell phone, and my friend, Iris. They took several stabs at a poem by Göran Sonnevi, delivering it differently each time.) The third stage, Bly writes, after having decided that the poem is for you, is to lay down the rough translation and go back to taste it again in its original language. Then you go single out lines and write them in your own idiom, no longer translating, but singing the poem yourself. The fourth state of translation is to discuss the third with someone who knows the language perfectly. And in the fifth and final state you bring in also the sound, the tone, as well. The original poem has a lot of nice sounds within it, - streaming, giant bells, Bly says - and if you don't carry this across you fail, and this is where most translators give up.

All of this carries the promise of translation – which is, as any poet will agree, a necessary act– Tranströmer himself says he learned poetry through the often-mediocre translations of Eliot, Trakl, and Eluard, all of whom he then, at the time of discovering poetry, thought of as Swedish writers. It might even indicate that the act of translating brings us closer to this second (or primary) secret meaning that we all along was moving towards.

April och tystnad / April and silence

Våren ligger öde. / The spring lay deserted.

Det sammetsmörka diket / The velvet dark ditch

krälar vid min sida / crawls at my side

utan spegelbilder. / without mirror images.

Det enda som lyser / The only thing that shines

är gula blommor. / are yellow flowers.

Jag bärs i min skugga / I am carried in my shadow

som en fiol / like a violin

i sin svarta låda. / in its dark box.

Det enda jag vill säga / The one thing I'd like to say

glimmar utom räckhåll / glimmers out of reach

som silvret / like the silver

hos pantlånaren. / at the pawn shop.

(ur Sorgegondolen, 1996)

This is certainly how I experience language – living in a city that speaks a multitude of them – with my mother’s tongue, my wife’s mother's tongue, my professional tongue, my private tongue, etc., etc. These languages all seem to have a temperament, a melody, a mindset, but none is in anyway a final solution. Herta Muller, who grew up in a German speaking village in Ceausescu-era Romania, and who's authorship, her point of view, is very much tainted by living in between languages, (in her case, one language that of a totalitarian regime), says in a conversation with the Paris Review that:

“the words have their own truth, and that comes from how they sound. But they aren't the same as the things themselves, there's never a perfect match. […] Every object becomes steeped with meaning. But the meaning changes with the experience of the viewer. […] “

In her first novel, Nadirs (1982), she describes the life in the village own idiosyncratic way of speaking. It’s not in a clear way a political novel, and the only censorship that the Romanian government placed upon it was the repeated removal of the word Suitcase. In this particular context, a word that suggest travel, which in turn could mean escape and indicate that the writer and reader wanted to leave the paradisical socialism under Ceausescu, became the novels most politically loaded word.

The point I’m trying to make is that if language is a unifying element, it will also be used to divide and isolate. The most exhilarating example is perhaps the American poet and playwright, Edgar Oliver, who grew up, due to the eccentrics of his mother, speaking French in Savannah, Georgia. When he and his sister Helen in their early twenties escapes their abusive mother to Paris, they realize that their French didn't correspond to the French they spoke at home. So, they learnt the Parisian way of speaking, but while doing so, they erased the memory of their childhood language. In the closeness of languages, the weaker one gets blurred and disappear. Through this act they lost the language of their childhood forever.

Proceeding Night Vision none of Tranströmers books were translated into English (Only the title poem of Den halvfärdiga himlen was in 2008 released as The Half-Finished Heaven in translation by Robert Bly. Here again I take issue, since Heaven has a religious connotation that Sky does not. It's not the religious heaven, I believe Tranströmer is speaking of, but the one above us every day). This leaves us two of his core collections to speak of: Hemligheter på vägen, that Wikipedia generously translates as; Secrets on the Way, and, Klanger och spår, that they, less so, name, Bells and Tracks.

The first is a rather naive title, simple and probably correctly put as, Secrets on the way, while the second one is harder. When I registered this page, it was exactly this last title I wanted to name it after. Bells, I never considered, or at least not the bell itself, but perhaps the sound of the bell – which is what brings to mind when I read Klang. The bell rings. There is a ring to it. Here's the word, the act, that Tranströmer uses. That he then follows up with Tracks, (or Paths), make me think of the Arthur Russell album, World of Echo. Another image would be rain over a lake and all the small wavy rings created by the falling drops on the surface. I landed at the end on Sonorities, since like Klanger, Sonorities suggested something harmonious. I didn't mean for it to be the final solution. I took issue not so much with what it represents – but the sound and the feel of the word. KLANGER is truly more like echo, but melodic, and coming from sources unknown. The title Klanger och spår, suggest a type of tracing of the subconscious, which was something I set out to do starting this project. To focus for a few minutes each day and trace these thoughts that I normally brush away. The word sonorities do not reflect this perfectly, it is also difficult to pronounce, it doesn't have the beauty of the two syllabylles of klanger (or again echo) but finally, which is probably more true about the substack; I had to decide on one thing to move past it. It would have to do. (It was not until after I realized that Sonoroties only got used in the web address and not on the landing page – that still just says Jonas' substack - and so the whole ordeal had been useless).

Klanger och spår has a beautiful sonority to it. The two syllables and then the one. Klang – er och spår. In the poems Tranströmer repeatedly plays with this perspective. There’s an alternative narrative in everything and surprising turns in the text. Finding focus that then by a small shift in perspective becomes blurred – it's the almost feeling of discovery:

Jag står under stjärnhimeln / I stand under the starlit sky

och känner världen krypa / and I feel the world crawl

in och ut i min rock / in and out of my coat

som i en myrstack / like within an anthill

(Vinterns Formler, ur Klanger och spår)

och på kvällen ligger jag som ett fartyg / And in the evening I lay like a vessel

med släckta lysen, på lagom avstånd / with the lights turned off, at a good distance

från verkligheten, medan besättningen / from reality, while the crew

svärmar i parkerna där i land / swarms there in the parks ashore

(Krön, ur Klanger och spår)

jag kommer för sällan fram till vattnet. Men nu är jag här, / I get down to the water too rarely. But now I am here,

bland stora stenar med fridfulla ryggar. / among the big boulders with peaceful backs.

Stenar som långsamt vandrat baklänges upp ur vågorna. / Rocks that has slowly walked backwards out of the waves.

(Långsam musik, ur Klanger och spår)

fantastisk att känna hur min dikt växer / Amazing to feel how my poem is growing

medan jag själv krymper / while I myself is growing small

den växer, den tar min plats / it grows, it takes my place

den tränger undan mig / it pushes me away

den kastar mig ur boet / it throws me out of the nest

dikten är färdig / the poem is ready.

(Morgonfåglar, ur Klanger och spår)

The other night we were hosting some friends, and as the night was winding down, and the rain had finally passed, we went up on the roof top to smoke cigarettes and enjoy the breeze. My Belarusian friend Dima was in charge of the speaker. He played a song from his country, Alexandria, and I asked him the meaning of the song. He translated one phrase: “he was walking down the road when he saw three pine trees, and then behind them, Alexandria”. This was all I knew. Yet, as I was laying there, so close to sleep and so far from myself, the song was completely clear to me. Singing is a language that goes beyond language and resonates with the body more directly, without the strain of narrative. Nietzsche described in the Birth of Tragedy the most powerful moment in theatre, when during the roman theatre, the narrator separated from the choir and sang the solo. According to Nietzsche, the existence of a narrator made the audience, dedicated to the faith of the narrator and not their own, able to follow to the mad peaks of emotion that the choir kept chiming out. There is something in language that maintain an otherwise unruly and much more emotional realm of life (the Dionysian , in the language of Nietzsche). And so, in the end is it the meaning of the words, or is it how they are communicated? In Mutal Aid, another playful philosophical work, Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin observes, describing the wildlife around a Siberian lake, how different species play and work together, protect each other from harm. In a beautiful part he describes how different breeds of birds sings together, calling out from their posts around the lake.

The translation of language, the moving between one and the other, the activity of circle the source of meaning and understanding, a kind of reaching into the dark, is best painted I believe, in this image by Kropotkin, of different species calling across calm dark surface of a lake.

Annie Dillard, who in the 1970’s lived in the Appalachian Mountains on a similar trip as Kropotkin’s, writing her killer memoir Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, observes something similar, asking the question which is really there from the beginning:

Today I watched and heard a wren, a sparrow, and the mockingbird singing. My brain started to trill why why why, what is the meaning meaning meaning? It’s not that they know something we don’t; we know much more than they do, and surely they don’t even know why they sing. No; we have been as usual asking the wrong question. It does not matter a hoot what the mockingbird in the chimney is singing. If the mockingbird were chirping to give us the long-sought formulae for a unified field theory, the point would be only slightly less irrelevant. The real and proper question is: Why is it beautiful?